Category: comics

The Unknown Rogues

Stupid Things I’ve Always Wondered About #28193

Remember the old Batman TV show? Of course you do. Remember the opening credits? Probably, but not as well as I do. As a kid the credits fascinated me, because they were the only cartoony aspect of the show (which, of course, was as camp as Christmas, but that’s irrelevant to this post).

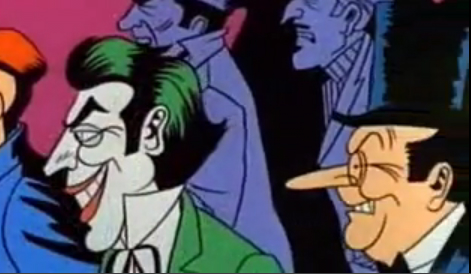

Anyway, during the credits, we see a large crowd of villains approaching (off-screen) Batman and Robin, only to have their asses handed to them, vis a vis onomatopoeic blows that cause them to fly through the air. Most of the bad guys are generic hoodlums and 40s film-style gangsters, but there are a few recognizable faces in the foreground. The Joker and Penguin to name two, plus,a few seconds later, someone who I assume is Catwoman.

Joker even re-appears after being severely mutilated by the comical Dark Knight.

What always bothered me were three of the bad guys appearing in the crowd. They seemed liked standard costumed antagonists, but despite all my useless comics knowledge, I couldn’t for the life of me identify them. It drove me nuts. The first two appeared to be some sort of anarchist/hippie mad scientist, and a guy in a scaly mask… or perhaps it was chainmail. Maybe he was an early appearance of Kobra (if you know who I’m talking about, you are a big damn geek).

A few second later, this guy turns up. He’s apparently some sort of serial-killing klansman rapist, or maybe Buckethead, or both. For extra geek cred I’m pretending that’s Clayface II behind him.

So who are these guys? Yes, the easy answer is that they were just generic bad dudes whipped up by the animation team to fill space. Maybe Killer Moth was too hard to draw. I’d prefer to think they’re secret Batman villains lost to the annals of time. Sure. If nothing else, they remind me of the background archenemies on the Venture Brothers. Maybe Grant Morrison will revive them.

For My Next Trick, I Will Fight Crime with This Photograph of a Gun

I certainly won’t say that Molly Norris should have censored herself (especially considering the dweeby innocuousness of her own cartoon), and that she needed to placate the world’s fundamentalist freaks. That just lends ammo those who think honoring other religions’ points of etiquette is the same as mailing plutonium to bin Laden.

I certainly won’t say that Molly Norris should have censored herself (especially considering the dweeby innocuousness of her own cartoon), and that she needed to placate the world’s fundamentalist freaks. That just lends ammo those who think honoring other religions’ points of etiquette is the same as mailing plutonium to bin Laden.

No, this is more a case where someone should have intelligently picked her battles and waged a propaganda war more wisely. In America, yes, we have a right to draw pictures of Mohammed… but MUST we? If drawing a picture of the prophet could retroactively prevent the twin towers from falling or lay waste to al Queda from top to bottom, I’d be at the kitchen table, day and night, with my notepad and Sharpies. As it stands, drawing, and putting out a call to draw Islam’s founder, is about as intelligent and effective in the battle against terror as giving the finger to Muslims worldwide.

Here’s the main problem with First Amendment shouters who demand the “right” to draw Mohammed. Say there’s a fellow on your block who’s a real bad seed—nasty, violent, and dangerous as all get out. You want to stop this guy’s reign of obnoxiousness, so what do you do? Right. You find a picture of his beloved grandmother, transfer it to a t-shirt above the words, “FILTHY GODDAMNED WHORE,” put it on, and march over to his house and cockily parade out front. Ha ha! Satire!

After making a few circuits, it becomes apparent that the surrounding homes are occupied by the rest of his family. Real salt of the earth types who’ve disavowed their ne’erdowell relation, but nevertheless love their grammy dearly. Consequently, as they sulkily stand on their porches and watch you march, you suspect they’re not happy with you at all. In your freedom blow-striking you’ve managed to alienate much of the neighborhood.

Oops.

But hey, you sure got under that guy’s skin. So much so, he’s coming over to your house tonight with a shotgun. He’s absolutely wrong to do so, but as the shotgun’s buckshot and gases expand your skull to twice its normal size, at least you can take heart in knowing you did the right thing. Which was to… Uh… Wait, it will come to me.

And that’s the dividing line between striking a blow for freedom, and simply being a impolite and delusional doofus.

Harvey Pekar Made Me the Man I Am Today (Sort of)

Harvey Pekar died yesterday. If the name doesn’t ring a bell you probably weren’t a comic collector in the 80s and 90s, or you missed the film version of Pekar’s comic American Splendor where Pekar was played by Paul Giamatti (accompanied by James “Doc Venture” Urbaniak and Judah “30 Rock” Friedlander as Pekar friends R. Crumb and Toby). Pekar was an irascible writer and jazz critic who fell into comic-making. It helped that he was friends with R. Crumb, who illustrated several seminal American Splendor stories and covers in the early issues. Starting in 1976, Pekar—a file clerk at a veterans hospital for much of his life—wrote stories about his daily toils that other cartoonists illustrated. Once a year, American Splendor came out, bearing stories about Pekar’s record-collecting, job travails, home life, and general philosophizing (a friend referred to him as a “blue-collar philosopher,” which suited him well).

The critics and mass media took notice of Pekar in the mid-80s after Doubleday released a trade paperback anthology of his work. Comics were coming into their own then. Frank Miller created the Dark Knight (which is why people think of Christian Bale before they remember Adam West when they hear “Batman” now). Alan Moore was re-imagining comics with Swamp Thing, Watchmen, and Miracleman. Art Spiegelman was midway through Maus. Neil Gaiman shimmered into existence with the Sandman, and Dan Clowes, Seth, and Chris Ware were warming up in the minor leagues.

Harvey, however, had been going at it for awhile, and on his own dime. He published every issue himself, paying the artists for their work, and distributing the comic strictly by mail and word of mouth. This was during an age when comics were still the exclusive province of dorks, and it was unthinkable for normal folks to consider curling up with a comic, whatever the subject. The man thanklessly toiled in comics Siberia for many years, only emerging once in a while to appear on The Late Show with David Letterman.

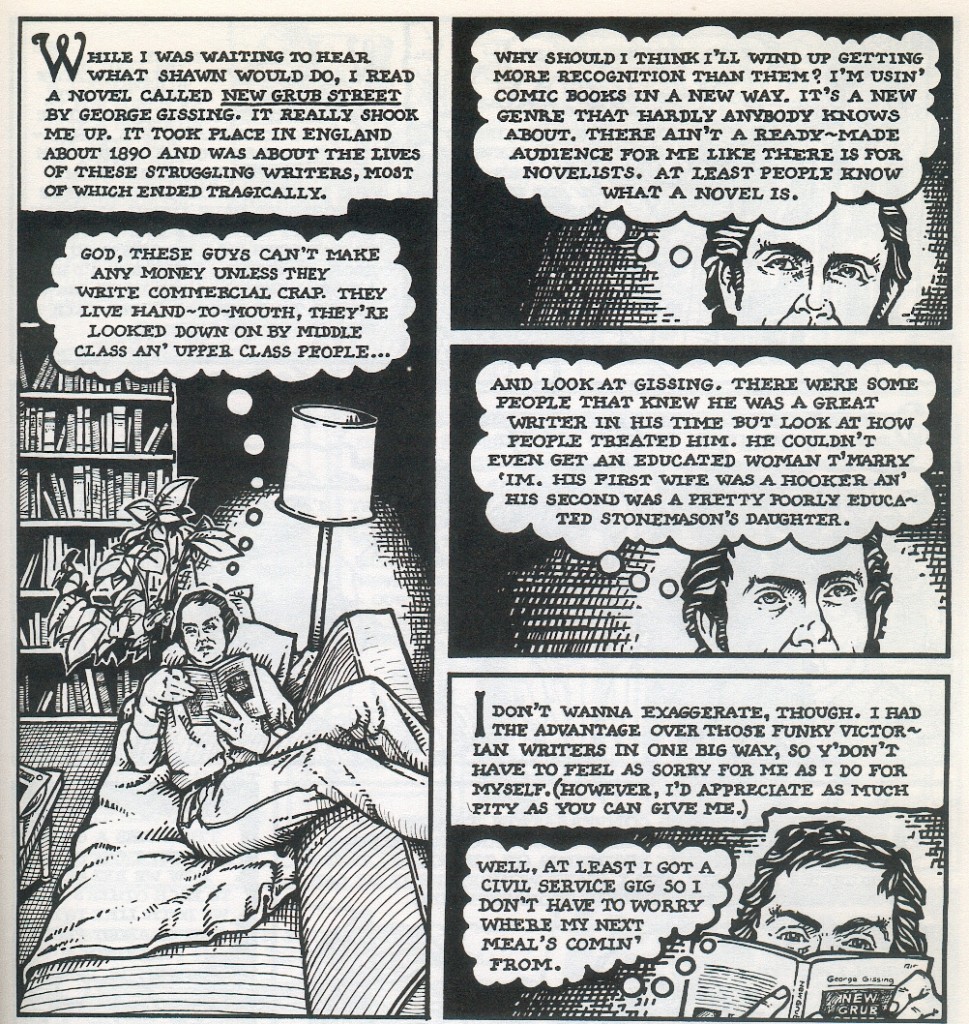

(This story led to me reading New Grub Street, which remains one of my favorite and most influential books.)

I heard about Harvey and American Splendor through a friend of a friend. He had a copy of the trade paperback, which I borrowed and devoured. I was, as you can imagine, different from most kids my age. Yes, I did the superhero thing through most of grade school and high school, but I needed something smarter. Then my friend (and his friend) introduced me to what we called, without irony, “alternative comics.” Alternative to what, you ask? DC and Marvel, and the adolescent male fascination with god-like men and women in spandex. Much of our taste was informed by the Comics Journal and Gary Groth’s take no prisoners criticism (which, when I read it now, reads more like a desperate, fretful, flailing attempt to be taken seriously), but while my friends took the hard-nosed “This Is Good/That Is Bad” approach, I just went with my gut. To this day I still don’t see what was so fantastic about Love and Rockets, though older me can appreciate the series’ lovely art. Comparatively, I saw something in the initial googiebation style of Dan Clowes’ Lloyd Llewellyn that bespoke greatness. Much of my taste and personal philosophy developed during this period, and American Splendor contributed to it in no small way.

Most reviewers, positive and negative, harped on Pekar’s everyday approach to storytelling. His life wasn’t adventurous; hell, most of the time it wasn’t even interesting in and of itself. Stories revolved around collecting jazz records, grocery shopping, finding a girlfriend, arguing at work, and so on. This was before a slew of GenEx cartoonists took Harvey’s idea and began churning out tales of their hand-to-mouth existences, toy collections, shitty dietary habits, and masturbation sessions. The difference was that Pekar was an introspective American polymath with a hardscrabble background. His type of personality and viewpoint, informed by the Beats, Yiddish culture, and old school lefties, isn’t so common anymore.

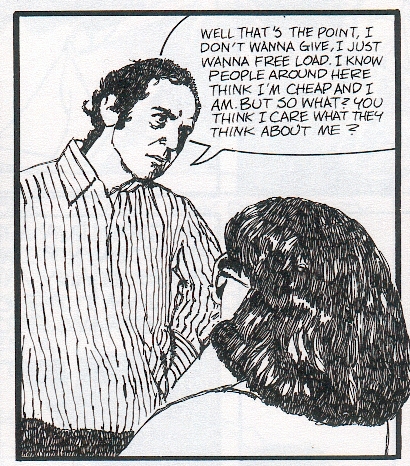

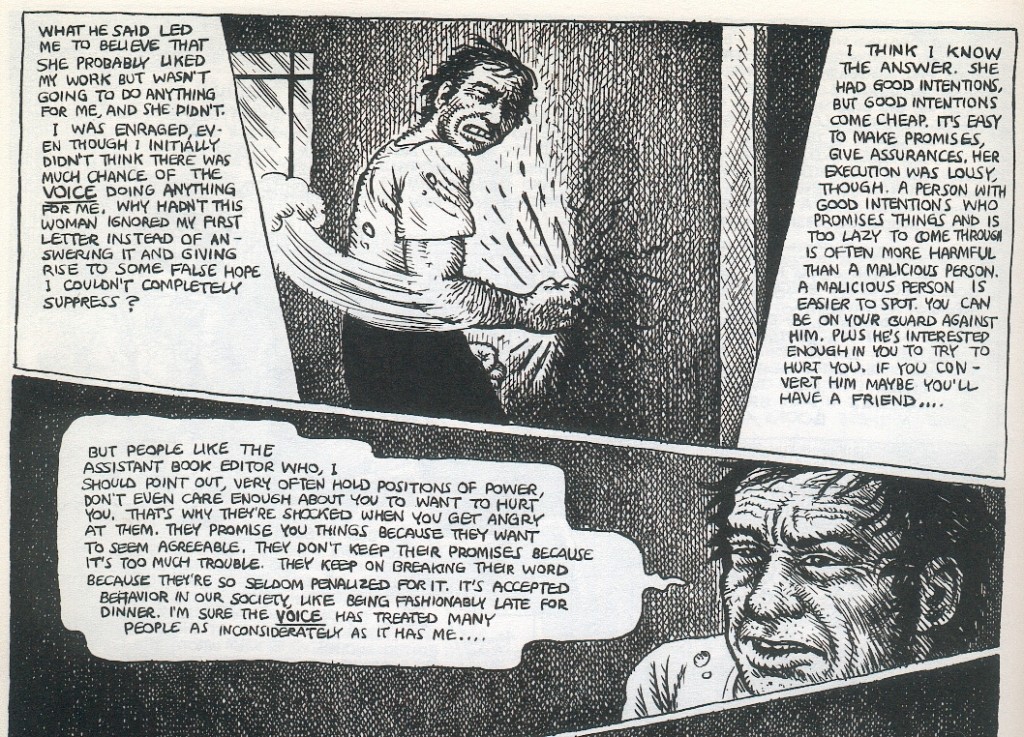

Pekar could be a major pain in the ass in his stories. Back when I was writing for a comic zine I was both in awe of his work and vexed by his selfishness. His worst comics usually dealt with his cheapness. One demonstrated how he kept crossing a street in New York to get free candy bars from street hawkers, filling an entire shopping bag. Intended to be humorous, I’m sure, it only seemed self-serving (though I did pick up the phrase “I gotta make hay while the sun shines.” from the comic’s final panel). Likewise the strips where he bitched about being ill-treated and unappreciated by editors, or, more memorably, on the Letterman show seemed like unreasoning self-immolation to my young, unpublished self. Re-watching that clip and rereading those old stories, however, after about 20 years of being a published writer, I found myself sympathizing with Pekar. The interviews aren’t Letterman’s finer moments, and while Pekar comes off like a grouchy nut, they reveal what a shallow fratrat Letterman could be back before the heart attack, baby, and blackmail attempt. Dave wanted Harvey to be a performing monkey—some crazy crank pulled off the street and bull-baited into crazed rants about not getting free donuts or what-have-you. Harvey wouldn’t have it, choosing instead to call out NBC’s parent company, GE on their evil ways. By not playing the game, Pekar was one of the few folks to strike Letterman dumb, and while I’ll always love Dave’s comedy, he needed to be taken down a peg or two back then. Banning Pekar for several years did not impress me, nor the nasty remark about Pekar’s “little Mickey Mouse weekly reader.” As it turned out, Pekar sold no more copies of American Splendor after appearing on the Late Show than he usually did. So much for the brass ring everyone kills themselves to reach.

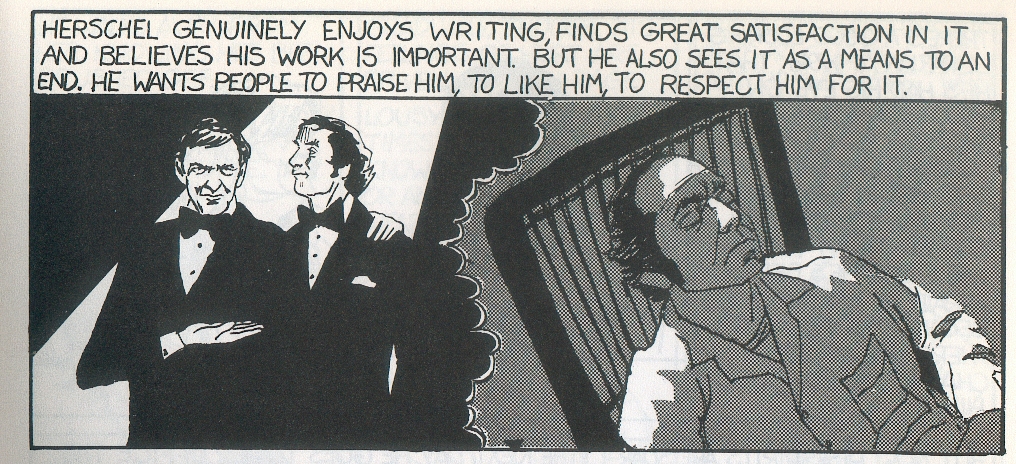

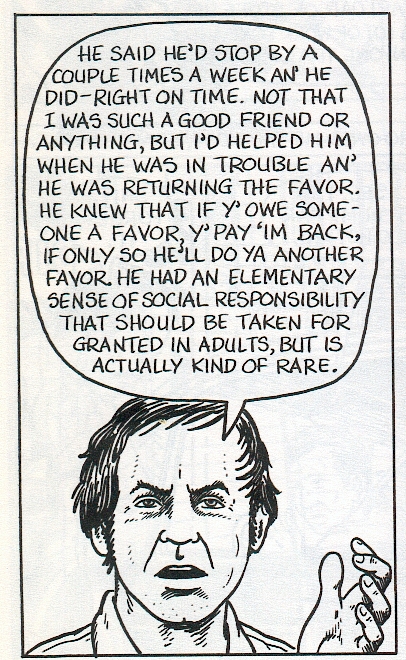

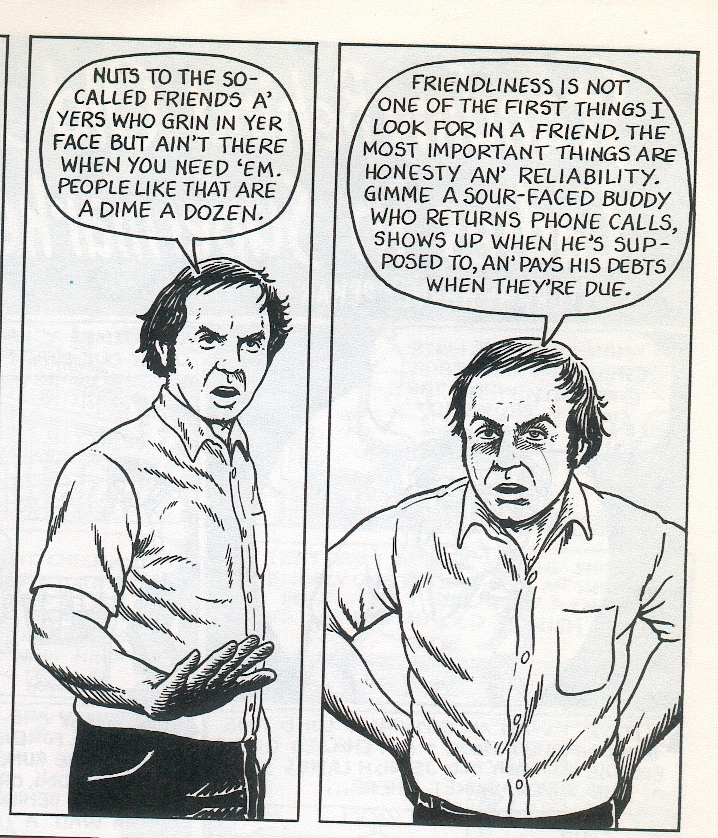

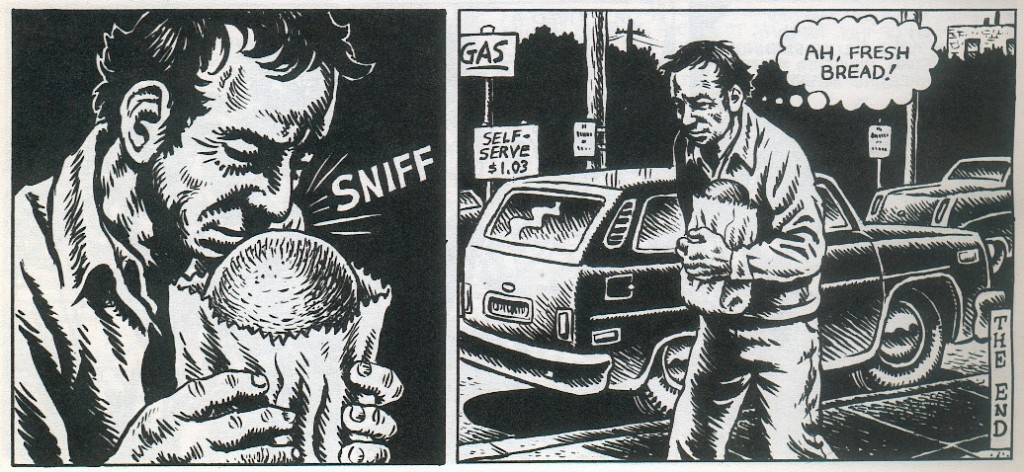

Above all, I liked Pekar’s pragmatism. When he presented a thought on morality or manners, it was a rough-hewn jewel. The below panels still come back and speak to me after 25 years.

(Yes, John. I remember that Mike M. picked some of these panels too.)

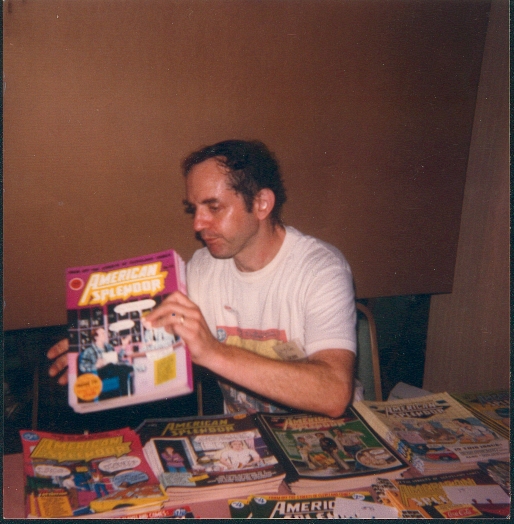

I saw Harvey exactly twice, I think. But I might be splitting the same encounter into two separate ones. The superhero-loving fans at the 1986 Comicon didn’t know what to make of Pekar. As I recall, the fanboys swarmed Howard Chaykin, Steve Rude, and George Perez’s tables, but Pekar and his wife entertained a small group of four folks, three of whom were me and my friends. Pekar’s wife, Joyce, as I recall, was ranting about the appearance of the cover of American Splendor #4 on the back of a Dr. Demento LP (“That’s like fucking with MICKEY MOUSE!” she shrieked), and they chatted a little bit about sending the good doctor a cease and desist letter. Later on, when the “crowd” thinned out, and the somewhat scary Joyce had left, I walked over to Pekar’s table and asked him to sign my trade PB of American Splendor. “Sure,” he said, signing it with a simple, “To Dan, Harvey Pekar.” “I love your work, ” I opined with startling originality. “Well, thanks, man!” Pekar rasped. Then I told him what my favorite stories were: “How I Quit Collecting Jazz Records and Published a Comic Book with the Money I Saved” and a few others. I mentioned loving Crumb’s work, though I’d only just started collecting reprints of his underground comics (again, this was pre-Internet, when complete compilations of most comic artists’ work weren’t readily available). “Yeah, Crumb is one of America’s finest cartoonists,” said Harvey, and he went on to describe his friend in large, historical terms. We chatted some more, and then I asked him if I could take a picture or two with my dopey little Instamatic for the comics-based amateur press alliance I wrote for back then. “Sure, sure,” said Pekar. Before taking this one he asked if he should be doing something. “Whatever you like,” I said. So he started stacking American Splendors. “All right! Harvey Pekar action shots!” I said, which made him chuckle.

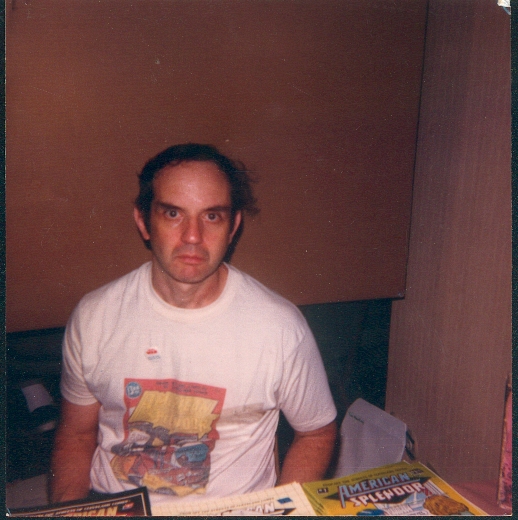

Then I took this shot, which pretty much says it all about Mr. Harvey Pekar.

It kills me that, in these pictures, he’s only about four years older than I am right now.

A week after the con, I sent Pekar a fan letter, money and an order for a few more American Splendors, accompanied by the photos. He wrote back something like, “Dan, Thank you for the photos, which were good ones. Please pick an issue of AS of your choice.” Naturally, I was flabbergasted. For my poor 18-year-old self, this was incredible largesse… and from a TV celebrity no less! There’s that “elementary sense of social responsibility,” or as I wrote back, “Quid pro quo LIVES!”

R.I.P., Harvey. I haven’t followed American Splendor for quite some time, but I have to say that I’ll miss the man. He made comics a lot more interesting.