Sturgeon’s Law states that 90 percent of everything is crap. Kelly’s Corollary adds that 99 percent of that remaining 10 percent is simply good. In art, good is largely preferable to bad—save in the case of something being “so bad it’s good”… but that’s another matter. Good is enjoyable, intelligent, savory, and consistently acceptable, and that’s just fine. Where we run into a problem is when good is inappropriately celebrated as extraordinary.

Sturgeon’s Law states that 90 percent of everything is crap. Kelly’s Corollary adds that 99 percent of that remaining 10 percent is simply good. In art, good is largely preferable to bad—save in the case of something being “so bad it’s good”… but that’s another matter. Good is enjoyable, intelligent, savory, and consistently acceptable, and that’s just fine. Where we run into a problem is when good is inappropriately celebrated as extraordinary.

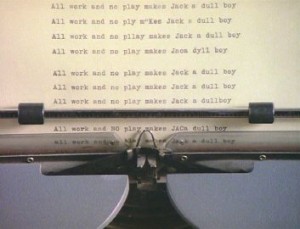

Good is never extraordinary. Good doesn’t excite or inspire people. Good doesn’t break new ground. Good rarely stirs up emotions. We leave the theater after viewing a good film, we finish listening to a good piece of music, or we put down a good book, and we say, “Well, that was good. Very good indeed.” And we tell our friends how good it was, and that they should enjoy it, because, damn, it was good.

Then after a short period of time, someone in a high position declares this work isn’t just good… Why, it’s great.

Then things get nuts.

The media immediately reports on this great thing, trying to crack its secrets by speaking with the people involved in it, cross-examining and poring over every segment of its existence, and extolling it as a work that will straddle the Rhodes harbor for all eternity.

Soon after, everyone is talking about the work in transformative terms. It’s no longer merely an entertaining experience, It’s become a perfect object wrought by seraphim working under God’s eyes. It will change the way we look at things. Upon viewing, you will orgasm mentally.

You’ll notice a certain consistency in the topics covered by these works, and in the names and credentials of those who produce them. Likewise those promoting the works, and the persons you know who extol them. This applies to high and low culture, by the way.

Does this invalidate the goodness of the good work? No, but it creates a climate in which a truly good work faces either (1) immediate, unquestioning approval, or (2) immediate, crushing disappointment and annoyance in those who don’t “get” it. Ah, but this, thereby, creates controversy, which is the second wave of promotion. The work is secondary to the arguments it generates by this point in time.

The only true measure of a work’s greatness, goodness, awfulness, or obscurity, of course, is time. Obviously, this is borne by the number of people who can be convinced of a work’s greatness over the years, decades, and centuries. One way is to let the subject review and assess the work on their own, according to its merits and their personal checklist of what makes for a good work. The other way is to create an perpetual promotion machine. This is, facetiously, a game of temporal telephone. The scholars, critics, and investors (now that copyright can extend for ridiculous periods) constantly promote the work’s virtues to, in the case of the university system, a captive audience, or, in the case of the aesthetic cult, those seeking constant validation of their beliefs and tastes. Meanwhile, as with telephone, changes in social mores, language, political upheaval, and more subtly change the perception of the work, and its original intent and meaning become lost. Which is just as well, because for a work to survive and be cherished as good, et cetera, it must remain organic and mutable. The perpetual promotion machine, however, insists on just one interpretation. Tell me you didn’t have a teacher who stuck to his or her guns when you disagreed with their interpretation of a work.

By this measure it’s interesting to step back and view what good to great works have survived, comparing them to what is considered good/great now. Why do Ishmael, Anna Karenina, and Sherlock Holmes persist? Why is Casablanca still an amazing film? In comparison, and to tip my hand to my ulterior motive, how likely is it that any of Aaron Sorkin’s stereotypes with their staccato clevertalk will survive into the next century, much less be considered extraordinary? I don’t know. Nobody knows. But it will be interesting to see what happens when the current crews of aesthetic roustabouts are gone, no longer there to drive in the stakes, hoist the ropes, and prop up the circus tents.