Note: If you’re wondering why it looks like a Cracked magazine article, it’s because I pitched it to them first.

by Dan Kelly

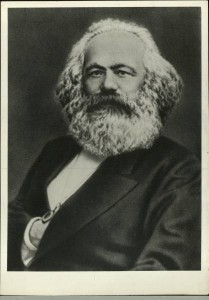

Unless your parents favored tweed suits with elbow patches and made you practice arpeggios eight hours a day, it’s likely your most memorable classical music experience happened when Hans Gruber’s goons cracked the vault to Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy”. Fair enough. Classical music reaches most folks through the media, turning certain “greatest hits” into sonic shorthand for action, grief, war, or what have you. You may not know Thomas Tallis’ glorious Spem in Alium, but you’ve surely whistled Beethoven’s Fifth. For a centuries-old musical genre, however, while most folks can hum a few bars of Wagner, few can name any composers beyond the usual batch of grumpy-looking Germans.

Pictured: Ludwig von Beethoven, composer of the “Moonlight Sonata,” the Eroica symphony, and a bit of the old ultraviolence.

Jump ahead a century after all those Austrian fancylads, however, and you’ll find a few notable (and notably odd) composers you’ve probably never heard of, or ever even heard in any sitcom, flick, or cartoon.

________________________________________

6. Charles-Henri-Valentin Alkan

Was Alkan a quiet, retiring fellow who kept to himself, or just an antisocial freak? Stories persist describing the deeply sensitive composer as a Howard Hughesian recluse—minus the yearly nail-trimmings, pee jars, and Mormon bodyguards. Evidence suggests though that if you were chummy with the man, he clasped you to his bristly bearded bosom. He was neighbors and good buddies with Friedrich Chopin, for instance, and when poor sickly Friedrich died at 39, Alkan took on his students. Hardly a hermit’s life.

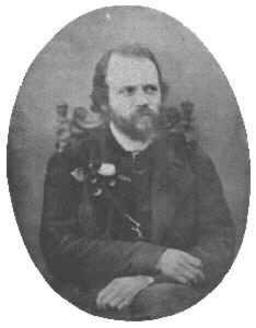

You have to wonder about Alkan’s social skills though after viewing the only pictures of the man in existence. For example, this is the warm, fuzzy one.

This is the other.

Merde! Don’t you fuckin’ look at me!

Born Charles-Henri-Valentin Morhange in 1813 Gay Paree, Alkan adopted his father’s barbarian-like first name, Alkan, as his last. Daddy Alkan ran a music school, and trained his many children in music-making. Like 19th Century Tenenbaums, they all proved to be brilliant—but Alkan was the family’s shiny star. Taking up piano and organ at age six, he publicly performed his own pretty-good-for-a-kid work by the time he was a pre-teen. Hitting the concert circuit in his early twenties, Alkan was skilled enough to be ranked with the classical world’s Elvis, his good friend Franz Liszt, who claimed Alkan’s piano kung-fu was unstoppable.

Then, on February 8, 1839, Alkan’s son Delaborde was born. Problem was Delaborde’s mother, a student of Alkan’s, was married to someone who was not Alkan. From 1839 to 1845 Alkan stopped performing and disappeared into his work to avoid scandal, though he eventually returned to the stage, and acclaim, in 1844.

Four years later, his career suffered another hiccup. Expecting to be appointed to the prestigious position of head of the piano department at the Paris Conservatoire… he wasn’t. Annoyingly, an impressively mediocre student of his, was chosen instead. For extra nonkosher salt in his wounds, Alkan was Jewish, and Anti-Semitism probably factored in the decision. Come 1851 Alkan got a gig as the organist at the Paris Temple, but his dashed prospects caused him to retreat further into secrecy and himself, and he resigned soon after. After playing two concerts in 1853, he quit performing, left the scene, and became a semi-recluse for 25 years, at one point writing to a friend:

“I’m becoming daily more and more misanthropic and misogynous… nothing worthwhile, good, or useful to do…no one to devote myself to. My situation makes me horridly sad and wretched. Even musical production has lost its attraction for me for I can’t see the point or goal.”

This was not a happy Alkan.

While a genius, Alkan wasn’t clairvoyant, and made several poor decisions that affected his legacy. For instance, he scored numerous tunes for the pedalier, a piano played with both hands and feet. The instrument didn’t catch on, and as a result, a good chunk of his oeuvre can’t be properly played today. Alkan also planned to score music for the Bible. Yes, the whole goddamned Bible, from Genesis to Revelation. Unsurprisingly, it never happened. Alkan also wrote long, complex pieces that tend to frighten off today’s performers with their long running times and highly virtuosic demands. His “Twelve Studies in All the Minor Keys”, Opus 39, for instance, takes two hours to perform.

On the lighter side, one of Alkan’s better-known compositions was “Marcia funebre, sulla morte d’un Papagallo,” which translates as “Funeral March on the Death of a Parrot” the lyrics of which consist entirely of the phrase “As-tu déjeuné, Jaco” (trans. “Who’s a pretty Polly?”). Insert the inevitable Monty Python reference here, but know that Alkan’s illegitimate son kept a hundred cockatoos as pets, along with two monkeys for good measure. Not all of Alkan’s work was so glib, especially toward the end of his life. His dank, miserable tune “The Song of the Mad Woman on the Sea Shore” may have you sticking a shotgun in your mouth before the final measure.

Alkan lived to the age of 75, never marrying, and simmering in sadness. Rumored to be crushed by a bookshelf while reaching for a Talmud on the high shelf, research reveals he was instead trapped by a coat rack/umbrella stand. A day passed before someone discovered the maestro beneath. Not a more dignified death, but at least a more accurate one.

________________________________________

4. and 5. Peter Warlock and Ernest J. Moeran

Peter Warlock made damn sure he looked like a guy named Peter Warlock.

Phil and Ernest’s friendship was built on a foundation of three shared interests: composing music, riding motorcycles at breakneck speeds, and getting knee-walking, folk-song-singing drunk. They had their differences too, Ernest preferred to be called Jack, for one thing, while Phil went by the what-the-hell? name of Peter Warlock.

Before Marilyn Manson… before Alice Cooper… before Screaming Jay Hawkins… there was Peter Warlock—yet another musically inclined geek with a goofily sinister name. Still, props to Mr. Philip Arnold Heseltine for giving himself a brutally metal nom de guerre in 1918, back when people were still gullible enough to ask if he was a “real” warlock. He certainly played the part. You probably haven’t heard of Pete because even though he wrote some lovely tunes in his short life, he was too busy getting smashed, smoking dope, dabbling in the occult, banging women, and writing dirty limericks about his enemies to create works that captured history’s eye.

Like many a brash, daring rebel who rejected conformity and society’s straitjacket moral codes, Philip Heseltine was a rich kid. He attended the creme de la creme of British schools, but quickly lost interest in his studies, leaving Eton and Oxford for a music criticism career—something you could do for a living in the 1910s, apparently—while figuring out what he wanted to be when he grew up. Phil was good at musical criticism. Too good. Phil Heseltine knew what he liked, and he savaged anyone in print and letters who didn’t meet his standards or pissed him off.

The name change to Warlock was more of a business decision than a swearing of allegiance to Lord Beelzebub. After years of smack-talking publishers, Heseltine composed a few songs and submitted them as Peter Warlock to a publisher he’d previously crucified. To his amusement, he made the sale, and from thenceforth he wrote articles, books, and criticism as Philip Heseltine and music as Peter Warlock.

Peter Warlock was the Doctor’s worthy adversary.

Warlock eventually grew an evil Spock beard (referring to his goatee as his “fungus”), learned at the feet of a constantly dying composer named Bernard Van Dieren, and then moved to Ireland to avoid the draft. At some point Pete started in with the occult-dabbling. Sorry, he wasn’t a black-robe-wearing satanic high priest engaged in virgin-sacrificing, baby-eating, and succubi-screwing. Mostly he participated in slumber-party stunts like automatic writing, seances, and tarot cards. Regardless, he took it quite seriously, writing to friends about being privy to mind-blowing prophecies and secret knowledge. “Sure, Phil,” his friends said.

Overall, while you might not want to leave Peter Warlock alone with your teenaged daughter, he was definitely the guy to party with. Unless your name was Ernest J. Moeran that is. Then he was the guy who’d send you on a merry, boozy path to hell.

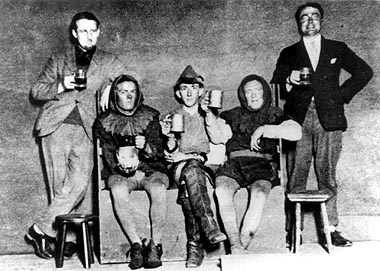

Pete and Ernie getting shitfaced with the Keebler elves.

Ernest John “Jack” Moeran matched his freaky buddy drink for drink when they shared a cottage in Eynsford, Kent, England, from 1925 to 1928. More impressively, he did it with a metal plate (and then some) in his skull.

Another prodigy, Moeran played violin and piano and composed music at a young age. After a stint at the Royal College of Music, he left school in 1913 to perform his patriotic duty in WWI. Favoring the feel of a fast hog between his legs, Moeran carried communiques by motorcycle in France. Things went swimmingly until May 3, 1917, when he got too close to the action and ended up with a headful of shrapnel. After head surgery as advanced as one might expect in 1917, Moeran got his skull plate, with some souvenir shards permanently stuck in his brain for good measure.

Moeran returned to Royal College in 1920, wrote pretty music, and began pub-crawling with Warlock to collect folk songs from craggy old-timers. In 1925, the two friends moved into the aforementioned cottage near a favorite pub and its crooning regulars, and for the next three years they composed, collected tunes, hosted parties, passed an ocean of alcohol through their gullets, and received regular visits from the bobbies when the carousing grew too boisterous for the churchfolk next door. Walking over from the pub one day, Warlock inexplicably told a group of kids standing near the church, “I’ll be your Jesus.” This earned him another awesome nickname from the kids: “Gentleman Jesus.” Warlock occasionally rode naked through the town on his motorcycle too, but apparently didn’t earn a nickname for that.

Perhaps through, gasp, black magic, Warlock held his hootch better than Ernest (though there are stories about him being steeped in rotgut, and incoherently muttering about God on the bathroom floor) and enjoyed a brilliantly creative period during this time. Regularly sozzled Moeran, on the other hand, cultivated a nice lifelong drinking problem that curtailed his composing. Even sadder, most of his notes and writings about British folk music, have vanished.

As hellraisers, you’d expect Warlock and Moeran’s compositions to resemble soundtracks to an Roman orgy hosted by Satan. Moeran transcribed a few naughty drinking tunes and sea shanties, yes, but their musical output, while occasionally melancholy and moody, was largely melodious and veddy, veddy British. Warlock the Antichrist liked to write Christmas carols, for crying out loud.

Perhaps predictably, Warlock died young at age 36, but not before cranking out a truckload of music, criticism, biographies of classical composers more obscure than himself, and a book titled Merry Go Down, an anthology of quotes and stories about great drunks in history and myth. He released the book under another pseudonym: Rab Noolas (get it?).

The circumstances of Warlock’s demise are sometimes described as “mysterious.” Considering the fact that, toward the end, he was jobless, broke, depressed as hell, and muttering about his best days being behind him, suicide seems likely. After putting his precious kitty outside with her dinner—Warlock locked the door, laid down, and died of asphyxiation, owing to a gas leak. The coroner himself couldn’t determine if it was a accident or suicide, but Warlock’s son Nigel (whom he had by his short-term wife, an exotic honey nicknamed “Puma”) suspected murder. Most music scholars dismiss this as pure piffle. Likewise claims by colleagues that Heseltine/Warlock’s shit-kicking hedonism and pretty little ditties indicated he had a “split personality,” or, presumably, an evil twin.

Ernest sort of enjoying a good smoke.

Moeran lived on and produced a few more pieces throughout the 40s, but continued to languish. He talked about writing another symphony, but it never materialized. His drinking worsened, his marriage crumbled, and his health declined. The war wound made itself felt, it is suspected, through memory lapses and poor concentration, and he worried he might be committed. On December 1, 1950, during a nasty storm, Moeran took a walk on a pier extending into Ireland’s Kenmore River. Witnesses saw Moeran suddenly fall into the sea. When his body was recovered, an autopsy revealed he’d suffered both a stroke and heart attack, killing him at 55 before he hit the water. Last call for Phil and Jack.

————————————————

3. Alexander Scriabin

Either he was moving through time or the Island was. Scriabin was never sure.

Scriabin was talented, brilliant, prolific, and absolutely nuts—but in a good way. Photos of the man recall LOST’s Daniel Faraday, while descriptions of his behavior suggest the composer’s brain also traveled through time, space, and all relative dimensions. A man who literally couldn’t sit still—friends said he preferred to hop and skip rather than walk, and once claimed he could leap off a bridge and float in mid-air—pre-Ritalin Scriabin hosted a legion of quirky behaviors and beliefs.

For instance, he either had synesthesia or something like it, visualizing the ebony and ivory side-by-side on his piano keyboard in various hues.

Elton John wanted his piano back.

While Scriabin’s work could be gorgeous and pleasant, his later pieces were a touch creepy and nervewracking. A man ahead of his time, he had inklings about atonality and Arnold Schoenberg’s theories by a decade or so. Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 9—nicknamed “Black Mass Sonata”—sounds like something Cthulhu improvised.

Another occult dabbler, Scriabin favored the ideas of mystic woo-woo purveyor Madame Blavatsky, putting them, at least, to a creative and productive end. Inspired, his most insane masterpiece was to be called the Mysterium. Scriabin planned a weeklong, multimedia project in the Himalayan foothills, to last from sunrise to sunset. Predating all the excesses of 70s prog-rock, Scriabin wanted to dangle bells from the clouds, shoot flames and light beams every which way, and release Smell-o-Vision scents during the performance. When the final note clanged, whistled, or blared the world would end and “dissolve in bliss,” and the human race would be replaced with “nobler beings.” Mind that Scriabin visualized this between 1902 and 1915, when the most advanced media at hand were Edison cylinders and silent movies. The man wasn’t just daydreaming—he dashed off 72 pages for a composition called Prefatory Action, a penultimate musical apocalypse designed to prepare humanity for the real Mysterium. When you hear it, it makes you wonder if Scriabin wasn’t onto something.

Scriabin wrote big too. One of his poems shows a mind inhabited by a cosmic cube of weirdness.

I am come to tell you the secret of life

The secret of death

The secret of heaven and earth

If you think this is too intense, try this:

I am God!

I am nothing, I’m play, I am freedom, I am life.

I am the boundary. I am the peak.

Unfortunately, Scriabin never lived to compose the Mysterium. He died of sepsis at 43, owing to either a shaving accident or an infected pimple. Born on Christmas and dead on Easter, he reportedly tried walking on water—as if all the above wasn’t enough of a mindfuck. As a postscript, his only child Julian was a child prodigy, producing an series of preludes before dying in a boat accident at age 11. Sad, but for all we know the Scriabins were aliens, and the human race came THIS close to symphonic extinction.

———————-

2. Havergal Brian

“Wait… I toil in obscurity until I’m HOW old? Jesus Christ…”

Havergal Brian personified the definition of insanity as doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. He also proved that patience is often rewarded. Another name changer, Havergal was born William, but he changed it in honor of a local family of musicians. His career started promisingly with a good gig as an organist, and funding from a rich guy who believed he was destined for greatness. A diligent worker, and entirely self-taught in composition, Brian composed constantly, cranking out music and drawing the admiration of classical heavy hitters like Richard Strauss (you know him from this), who called him “magnificent,” and Edward Elgar (you know him from graduation and college sex comedies). In 1909, at the tender age of 33, his cantata “The Vision of Cleopatra” debuted to great applause. The world, as they say, was his.

Suddenly the world wasn’t.

World War I broke out, making symphonies a lower priority in England. Furthermore, Brian acted like a total cad by cheating on his wife (with whom he had five kids), and knocking up his mistress (with whom he later had five more). Composing commissions dried up, and after his patron died he divorced his wife, married his mistress, and got a day job.

Most men might have given up by then, but not Havergal Brian, by God. He kept on composing in his free time, turning out piece after piece, song after song, and symphony after symphony—and not one had entered so much as a Salvation Army band’s repertoire. Brian couldn’t entirely blame Dame Fortune for his troubles. He stymied his prospects by writing symphonies demanding money and resources beyond the means of any but the largest orchestras. The Gothic Symphony alone required six choirs, four brass bands, and a 180-member orchestra.

But fame and fashion come and go and come back again. Brian returned to the spotlight in 1954 when BBC music producer Robert Simpson rediscovered his music and produced Brian’s Eighth Symphony for the radio. At the time the man was pushing 78, and most of what he’d written over the past 45 years had never been performed.

The belated adulation put Brian into overdrive, and from 1958 to 1968, he whipped up 20 new symphonies, for a lifetime total of 32. For perspective, that’s much less than Mozart (44 in 33 years) but way more than Beethoven (nine in 56 years)—though it’s quality not quantity that matters.

Turning 95, Brian was asked by the New York Times about his prospects and how he dealt with the slow, inevitable approach of the Grim Reaper, Havergal Goddamned Brian waved it off, replying he couldn’t die yet, because he’d just bought a new pair of pants. As it turned out the unstoppable son of a bitch lasted another two years.

——————————————–

1. Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892–1988) didn’t know you, but he thought you were a complete idiot. Don’t feel bad. He thought most people were idiots—at least in regard to music appreciation. Like his good friend Peter Warlock, Sorabji not only composed but also wrote a truckload of musical criticism. Like a record store employee he oodled over the music he liked (fellow shut-in Charles-Valentin Alkan, for example), and shredded what he hated. Sorabji also considered his music suitable only for a chosen few, and went to great lengths to ensure the “wrong” people never came close to playing or hearing his precious, precious notes. Cute and cuddly Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji was not.

He also looked like a record store employee.

While he didn’t change it for show-bizzy reasons, British-born Sorabji made a good call when he dropped his birth name, Leon Dudley, for a flashier appellation honoring his half-Parsi heritage. Another silver-spoon-sucker, Sorabji was privately tutored, and after a few short years of dazzling his instructors, trained himself as a pianist and composer. All by his lonesome, Sorabji learned enough to create some of the longest, most finger-breaking works ever composed.

An excellent pianist, Sorabji nevertheless rarely played out. Candid about his self-perceived short-comings, he eventually developed stage fright and a preference for performing for small groups of friends and fans. On December 16, 1936, after his final public performance, Sorabji heard one of his works played by someone else. Considering it not up to snuff (the pianist took an hour and a half to perform a 40 minute passage. Quelle horreur!) he forbade anyone from playing his ditties, under legal threat—until 1976, when he decided only pianist Yonty Solomon was worthy. During that time he rudely rejected interview requests, fed researchers disinformation about his age and past, and withdrew to a house in Corfe Castle, Dorset, England, with a sign out front stating “VISITORS UNWELCOME.”

That didn’t stop Sorabjji from composing. God no, the solitude spurred him on to crazy heights (and lengths) of soundscaping. Writing works for piano mostly, and increasingly inspired by Persian and Indian music, Sorabji’s work became huge and complex. Even his song’s names were long and twisty, somewhat resembling black metal album titles. His most well-known composition is Opus clavicembalisticum, which, played in its entirety, lasts over four hours. Opus clavicembalisticum was once recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest piece of music ever composed. A ridiculous statement since several of Sorabji’s other works clock in at eight hours or more. Hell, the title of his work Opus Archimagicum, Sequentia Cyclica Super Dies Irae ex Missa Pro Defunctis takes two hours to say out loud.

To be fair, Sorabji wasn’t friendless or even personally unfriendly (though famous picky people always seem to have their defenders). The man simply had high standards, and if you didn’t meet them, woe betide thee. A pre-Internet troll—albeit with an actual brain, fancier vocabulary, and knowledge of what the hell he was talking about—Sorabji regularly fired off sarcastic letters to classical music journals, railing against lousy music, bad taste, and those vile sons-a-bitches who dared to cough during concerts. For example:

“What is this demented balderdash about people not liking certain manifestations of what is called contemporary composition because, it is said, they don’t “understand’ them?

You don’t ‘understand’ caviar, trepang, or rotten goose-liver (alias Pâté de foie gras) you either like them, in the last instance, if your palate is sufficiently degraded and perverted, or you don’t.”

Oh, snap!

Why do I neither seek nor encourage performance of my works? Because they are neither intended nor suitable for it under present, or, indeed, any foreseeable conditions, and no performance at all is vastly preferable to an obscene travesty.

Oh no he didn’t!

Mr. Rutland with the charming kindness so characteristic of him, is far too indulgent towards those tasteless, ill-mannered, ill-bred coughers, brayers, snorters, barkers, who mar every concert everywhere. These odious creatures never make the slightest attempt to mute the revolting pulmonary, tracheatic, or catarrhal uproar they make; on the contrary, they open their faces to the fullest extent, giving free play to their pestilential rheumal clamour.

In short, Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji thought all your favorite bands sucked.

Finally, Sorabji is quoted as telling his fellow classical music weirdo Peter Warlock the following:

You claim that I write monstrosities which only the composer can play. What if they were meant only for the composer?

That much seems evident.

Mr. Dan Kelly has also been writing for years, and most of his work has never been seen. Unlike Sorabji, this was not a conscious choice on his part. He can be found at his Web site and Twitter account regularly fulminating against catarrh-uproarers. Thanks to Mr. Andrew Patner for suggesting Mssrs. Warlock and Sorabji!