“But there was more to it than just coping with such traumatic situations. In later life, despite being hailed by so many as an American genius, Vonnegut felt that the literary establishment never took him seriously. They interpreted his simplistic style, love of science fiction and Midwestern values as being beneath serious study.”

“But there was more to it than just coping with such traumatic situations. In later life, despite being hailed by so many as an American genius, Vonnegut felt that the literary establishment never took him seriously. They interpreted his simplistic style, love of science fiction and Midwestern values as being beneath serious study.”

Never minding that Vonnegut was due for an inevitable “Your great hero was flawed! FLAWED!” biography, there’s a common trope among successful cross-genre writers that’s always niggled at me. I’ve never understood the concern among such writers to be taken “seriously” by the “literary establishment.” What exactly does that mean, to whom do they refer, and what is the root and extent of their desire for acceptance? Can we assume David Remnick refused to go shoe shopping with Kurt? Did Kingsley Amis blackball him when he applied to the Junior Woodchucks in fourth grade?

The history of literature is a jittery timeline of yesterday’s young firebrands becoming today’s stodgy old poops, making sure the newer, angrier kids can’t sit at the big table until they’re old and grey (Kerouac died a broke drunk, while Burroughs became a chevalier of France’s Ordre des Arts et des Lettres), or grow willing to play according to the rules of the universities, lit journals, and writing workshops. Or so the story goes. In actuality, the world of literature has become so fractured and fragmented (and the need for validation diminished by the instant gratification of the Internet—nowadays even a halfway decent writer can have a bushel of fans and supporters), needing approval by the establishment seems charmlessly archaic. I remember the time I attended a party thrown by a certain well-known magazine. I spoke with an editor who gave me a pleasant, but head-patting speech of encouragement, telling me that if I worked really hard, maybe I’d get published by a real magazine like his. I wanted to tell him, “But… I’m published and already relatively content, chum. More recognition would be nice, but… Well, forgive me, but turning up in your slick yet tepid mag would feel like a artistic step back for me. Of course the check would be nice.” Yes, there might be one or two mags I’d sell my children’s souls for a chance to appear in (Car and Driver, why haven’t you ever called?), but overall I have no one I NEED to impress other than my friends, family, and myself.

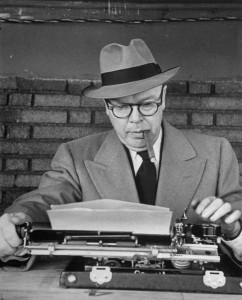

To me the best writers are the loners, Holed up in their attics, apartments, and cabins, they occasionally interact with their editors and publishers, but rarely attend the right cocktail parties (Capote notwithstanding, though that’s how that particular bird lost his way). They never needed validation. All the real work and gratification took place between their ears.

Reading about big-time writers like Vonnegut and Hunter Thompson complaining about a lack of recognition is both quaint and perplexing. It makes me wonder what exactly they were after since they were pretty well-recognized in their own lifetimes. It gets especially silly when the writer laments his lack of “acceptance,” despite the reprints, book signings, readings, honorary doctorates, hot, ready, and willing fans, commencement speeches, talk shows, multiple translations and anthologies, ongoing fluff assignments for big bucks, merchandising, royalties, film and TV cameos, inclusion in the curricula of a thousand thousand colleges, and insertion in the memory of every human being who read their work and heard them speaking to their deepest heart of hearts.

Recognition?

God bless you, Mr. Vonnegut, you imbued a phrase as simple as “And so it goes.” with immortality. And yet that wasn’t enough? Or was that compassionate grump act just covering up a basic, irritable crank?