The first time I ever spoke up here I was 12 years old and a student at St. Damian. I recited a reading for that week’s mass. As a quiet kid it was a big deal, and an attempt to break out of the shell everyone told me I was in. I did it without passing out or running away so…a major success. My homeroom teacher, however, gave me a typical back-handed compliment, “Good job, Danny. I just wish you could carry a microphone all the time so we could hear you.”

I don’t remember if I mentioned all this to my father, but I’m sure he would have been impressed that his introverted son made a game effort at public speaking. Bernard J. Kelly, of course, was an consummate speaker. If you met him, you remember that voice. Deep and distinctive. Able to cut across the noisiest room, but never obnoxiously so. That tremendous voice was diminished by Parkinson’s, but he was always able to make himself heard.

It’s an understatement to say he was an exceptional and uncommon man. Most only saw the topmost layer. The elegant gentleman with the sonorous voice. The politician who served Oak Forest in several offices, including mayor. The triple-degreed scholar who attended MIT and U of C, and pursued a career in law as a third act. All impressive. He always stressed and demonstrated a strong sense of duty and constant betterment.

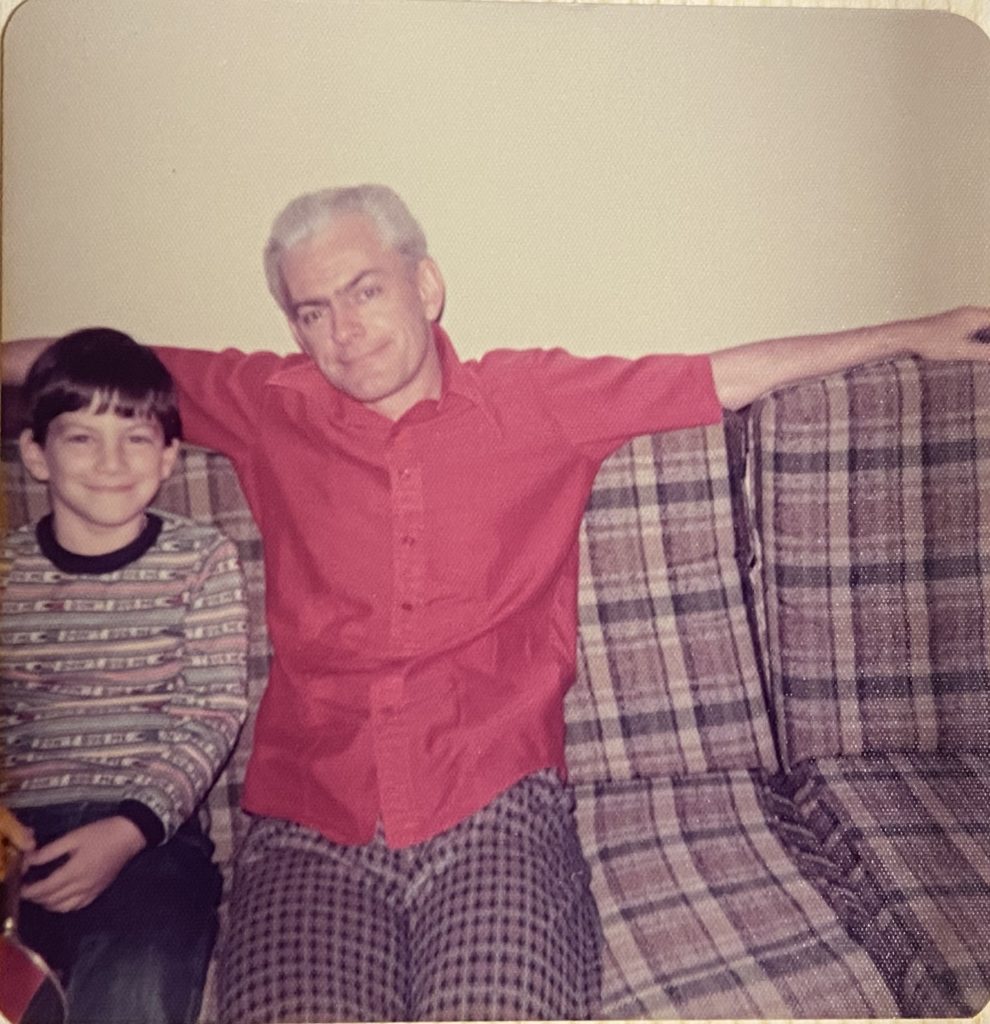

But what always stood out for me was Dad’s insatiable curiosity. Growing up I knew few adults with any interests beyond their jobs and sports. Dad, however, found life terribly interesting. He didn’t have a favorite subject. He had many. Politics, city management, geopolitics, war, water treatment, chemistry, the law, survivalism, science-fiction, cartoons and comics, and old movies… How many people can run a city and also hold forth on schlocky sci-fi and horror films? Very few, I think. When my friends met him they always said I made more sense. He was a very strange and very normal man. My hero.

As much as Dad could lecture on the above and other subjects, he was irritatingly tight-lipped about his past or personal matters. When he did share, it consisted of intriguing bits about old Chicago. His boyhood pet the rooster… Riding the streetcar to Riverview… Bicycling to Starved Rock… I think I recall him mentioning climbing onto the roof of the Museum of Science and Industry as a lad, but I can’t confirm that bit of derring-do. Maybe he wanted to discourage me from following in his footsteps. Regardless, Dad’s reserved nature never interfered with his desire to reach out and help others.

Despite what society suggests, loudness does not translate into effectiveness or admirability. As a leader and politician he was known for honesty, integrity, seriousness, and a deep intelligence. Amongst the plaques hanging on our front hall wall, I remember one with a gavel presented to Dad in gratitude for his service. The inscription reads, “Speak Softly and Carry a Big…” The quote is part of an African proverb favored by President Teddy Roosevelt. In full, it states “Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.” Meaning, negotiate peace, but show off your strength.

But Dad—who was fond of weaponry—never felt the need to strut, puff out his chest, or rattle his saber to get things done. He owned two sabers, by the way, so he could have. I imagine he brought Lake Michigan water to Oak Forest and helped the town grow from a village into a city through his usual tools of debate, diplomacy, and quiet strength. To my mind, and thinking of the many life lessons he imparted, the most impressive and important things in this world labor in relative silence. The atmosphere. The continents. Water. Forests. I suspect Dad would have made an excellent redwood

I wish he’d explored his creativity more often. He occasionally mused about writing a science-fiction novel, but I don’t know how serious he was about that. I would have read it. I remember a few times when he broke free of his usual stern persona. My happiest childhood memories of dad are of the times he allowed himself to be playful. When I had the chicken pox I lied there in my childhood bed, in the dark, miserable. He came home from work and visited me, still wearing his suit and tie. He asked me how I was.

“I have chicken pops,” I believe I said.

He took my Dapper Dan doll, uncapped a black felt-tip pen, and dotted Dan’s face.

“Now he has them too,” he said, followed by one of those fake “Ha ha ha’s” he uttered when he was joking around. I was delighted.

Another time we recorded sound effects for a classroom play together. H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man. We shared a love of the old Universal Classic movie monsters, so how could he refuse? In one scene, the Invisible Man smashes through a window to escape an angry mob. The sight of Dad in work gloves, using a hammer to shatter an empty whisky bottle over a garbage can while I recorded it with his Dictaphone amazes me still.

He had a dry wit; almost Saharan at times. But he also always had all the best words, excelling at toasts, spontaneous speeches, and everyday inspiration. My daughter Flannery tells me that when she was much younger, she told him she wanted to be a butterfly when she grew up. He informed her she couldn’t be one…but she was as beautiful as one already. If you didn’t know, when he visited Ireland, Bernard J. Kelly kissed the actual Blarney Stone.

Dad was a quiet but never passive presence. He kept himself to himself, but never too much. He was generous with his time and knowledge, and not just for the community. He was always there for us—JoAnn, Nancy, Loretta, Eileen, and me—attending band and choir concerts, spaghetti dinners, graduations, weddings, baptisms, business endeavors, elections, real estate closings, and more. He was especially there for Mom, whom he adored and thanked God for. While the word cuddly was never once used to describe Bernard James Kelly, his love and affection for Mom was palpable. Whenever he used the word we in a statement, he wasn’t affecting a Queen Victoria pose. He meant him and Mom. Just as often he meant the whole family. He chose us over an extended role in politics, for example. He made several wise decisions for our benefit as well. While Dad would rarely admit he was wrong, he always addressed his mistakes. He quit smoking. He gave up drinking. He added many more years and much more good to his and our lives as a result. I consider those two of his greatest accomplishments.

*****

Dad’s wood-paneled basement den was a place of refuge and inspiration for both of us. Two couches, a long table and folding desk I think he built himself, a battered gold upholstered chair beside a end table with a lamp…and hundreds of books on a thousand subjects on every wall. Books were revered in our house. I was given free rein of the library, and it was here that I discovered several writers and cartoonists I still admire: Ray Bradbury, Oscar Wilde, Charles Addams, Gahan Wilson, Mark Twain, and others. One quotation I recall chuckling over with Dad came from Mark Twain, who said:

“When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.”

I never had that experience. Even when we disagreed—and we disagreed more than once—I always knew my father was one of the wisest, smartest, most conscientious, and dutiful people I knew or ever would know. He was a thinker and doer who left the world and his family safer and richer for having known him. We’ll never see his like again, and we dearly miss him.

Take care, Dad.