Horror fiction is the only genre I follow with any consistency. I’ve had brief flirtations and extended courtships with genres like fantasy (I favored sword and sorcery during high school, but happily never after), mysteries (mostly the old pulp/hard-boiled stuff, though I’ve followed a few modern series), and sci-fi (briefly raiding my dad’s 40s to 70s sci-fi library—truthfully, it’s the only genre I find a bit silly). Horror, however, is my fictional wife, or at least my mistress.

Horror fiction is the only genre I follow with any consistency. I’ve had brief flirtations and extended courtships with genres like fantasy (I favored sword and sorcery during high school, but happily never after), mysteries (mostly the old pulp/hard-boiled stuff, though I’ve followed a few modern series), and sci-fi (briefly raiding my dad’s 40s to 70s sci-fi library—truthfully, it’s the only genre I find a bit silly). Horror, however, is my fictional wife, or at least my mistress.

I’ve been reading horror novels, short stories, and comics and watching horror films and TV shows since grade school. Arguably even before that through myths, ghost stories, and fairy tales. I followed a familiar path, starting with Poe, Bierce, Stevenson, Wells, and the other classics; reading through Stephen King’s output; discovering Lovecraft and Rod Serling’s circles; indiscriminately gobbling up every vault, haunt, and crypt of terror-fear-horror EC, DC, Marvel, Gold Key, and Charlton comics offered; falling in love with my literary queen, Shirley Jackson during college; and working through everyone from Ray Bradbury to Richard Matheson to Clive Barker to Mark Danielewski, and plenty of other hacks and auteurs in-between.

Between all that I watched my share of B-movies, monster flicks, cult classics, gore fests, and arthouse horror, and delved deeply into real life nightmares like serial killers and ickier/stickier subjects, and supposedly real life nightmares in the urban legend/campfire story vein. If it was disturbing, made my flesh creep, and had me hiding under the covers, I was interested—especially so. Why? Who knows? A slow imbibition of poison, perhaps, can do a body good. What does not kill me makes me stronger as I shudder.

The gist of this entry is that I’ve seen and read a lot of scary stuff. Most of it is forgotten, some remains, but a few bits and pieces have lurked for far longer, like dark flickering shadows in the corners of my eyes. Two in particular though, not only stuck around, for years I couldn’t be sure if I’d actually seen them, or if my mind made them all up. I’d like to share them, and if I’m worth a damn as a writer, I might even help you understand why they remained with me.*

*****

As indicated, my brain’s mouth has gobbled great greasy piles of fictional horror-steak, the quality of the meat running the gamut from terrible (as in awful) tales of terror that couldn’t scare a three-year-old, to pungent, succulent, juice-dripping stories that made my sense of reality slip a bit.

Just a little bit.

But just enough.

The latter are rare, their power depending on their originality, the writer’s skill, and my age while reading them. What scared me at age 10 wouldn’t make me arch an eyebrow at age 45, but like a chicken pox scar, some sensations remain scratched into my memory’s flesh. Hm, maybe not a chicken pox scar. More like a self-administered tattoo.

The fictional fears that stay with me are diffuse: Lovecraft’s description of Akeley’s cylinder recordings of the Mi-Go’s buzzing voices—use of recording technology as a false document to cause the heebie-jeebies decades before The Blair Witch Project, incidentally. The night burial of Church the cat in King’s Pet Sematary. The cool, low-toned fear of House of Leaves, when the protagonist stops and listens to the constant grinding and shifting of the walls, floors, and ceilings as the house remodels itself. Clive Barker’s “Dread,” which ends ludicrously, but has an exquisitely horrific extended photographic sequence featuring a vegetarian, a steak, and a locked room. No easy trick for a writer when they can’t show you the photographs.

Those are memorable bits, surely, but there are two that lingered, sticking to my brain like a black tumors, and metastasized over the years, become more terrible than I knew they could have been (this entry deserves turgid, overwrought metaphors, leave me alone!). Why did these moments become so exponentially freaky and terrifying? Mostly because I encountered them once, and then never saw or heard about them again. Even worse, no one I spoke to about them knew what I was talking about. A horror trope in and of itself!

I’ll wager most of the younger folks out there have no concept of the pre-Internet age, when pop knowledge wasn’t easily acquired. Surely, you could go to the library and get your fill of info on Benedict Arnold, Art Deco, wainscoting, or other “normal” topics, but try to locate an iota of info about an obscure TV show, film, writer, or book… good luck with that pal. In my youth, while looking for works by, say, Kerouac and Lovecraft, the four or five local libraries I had access to were only able to scrounge up Tristessa and The Dunwich Horror. As for other books by those writers, or just more information about the writers themselves, the librarians did their best, finding and photocopying a scattering of articles through reciprocity agreements with other libraries. Ultimately, they were found wanting. Think of that drought of facts, and compare it with today, when punching a few words into Google turns up rafts of websites about Jack and Howard that all but tell you what they had for breakfast on any given day of their life.

One more point, a seemingly strange point: while the info they turned up was sparse, they proved that Kerouac and Lovecraft existed.

Now, imagine trying to describe something you experienced briefly as a child, without benefit of verification through images, sound, or text. Just you, babbling: “There was this cartoon I watched every day as a kid, where this alien boy came to earth, and he had a medallion that gave him superpowers. And his worst enemy was a guy who threw a buzzsaw watch.” For years I described the show to kids in my own neighborhood, trying to find someone else who had watched it on UHF channel 44. “Uncomprehending” is too light a word for their expressions. It wasn’t until I took German in high school and met a girl named Ramona who’d also seen Prince Planet that I realized I hadn’t made it all up. That sense of doubt is weird enough for an innocuous (if hyperviolent) cartoon like Prince Planet, but it becomes cancerous with a thing that scared the hell out of you. I’m sure there’s a psychological term for it. Maybe the Germans call it by some multi-syllablic name.

But I lived until the 1990s, and I light a candle and say a prayer for Mother Internet for letting me know I wasn’t going mad when I rediscovered the following spookshows.

*****

As a kid, how old do you have to be before radio shows seem stupid and boring? I should experiment with my four-year-old son, and play The Shadow, The Whistler, Weird Circle, and other old-time radio shows for him before he becomes jaded. I’ll tell you one thing, I’ll sure as shit not play Arch Oboler’s 1962 Drop Dead! album—featuring reenactments of his 30s and 40s radio show Lights Out—within listening distance of the lad until he’s at least 10. Maybe 30.

As a kid, how old do you have to be before radio shows seem stupid and boring? I should experiment with my four-year-old son, and play The Shadow, The Whistler, Weird Circle, and other old-time radio shows for him before he becomes jaded. I’ll tell you one thing, I’ll sure as shit not play Arch Oboler’s 1962 Drop Dead! album—featuring reenactments of his 30s and 40s radio show Lights Out—within listening distance of the lad until he’s at least 10. Maybe 30.

I still remember how queasy I felt after hearing the LP at a friend’s house one long-ago Halloween. If you’ve heard of Oboler’s show, you probably remember one story in particular: “Chicken Heart.” Everyone remembers “Chicken Heart.” With that title how in God’s name could you not? Orson Welles may have convinced the rubes that the Martians had landed, but Oboler left a bloody wet thumbprint of terror on the brains of multitudinous youths, including Stephen King and Bill Cosby, who did a routine on the show. I won’t summarize “Chicken Heart”; it’s best experienced through the first link. Certainly, it’s ridiculous—absurd even—but there’s something there, something grotesque and wrong. Thump-thump… thump-thump… thump-thump…

For me, Oboler’s scariest, freakiest skit was “The Dark.” “The Dark” barely has a plot. Scary stuff just…happens. From memory…Sam the cop and a psychiatrist are called to an old abandoned house (is there any other kind in these stories?) because the neighbors, presumably, heard screaming and shenanigans taking place. The cop and the doc walk in and discover a madwoman, given to bursts of cackling, shrieking laughter that will drill through your head. Something stirs in a nearby room, and when the doctor, to the cop’s chagrin, opens the door they discover… a man… TURNED INSIDE-OUT! A monster shows up, as monsters do, in the shape of a shadowy mass that acts more like a pitch-black amoeba. Listen to the link before proceeding further. I’ll wait.

*****

“The Dark” is scary. “The Dark” is also, under scrutiny, stupid. Unlike many fictional monsters, our shadow beastie makes no damn sense whatsoever. Let’s pretend a person could survive the initial, incomprehensibly painful shock of the act, not to mention that a person could be “transposed” (they can’t, sorry), and ask, what is the creature’s motivation? Whether sentient or non-sentient, why does it do what it does? According to the presented evidence, it doesn’t perform full-body prolapses to eat, defend itself, or even to meet some magical/ritualistic purpose. Notably, it does not properly kill its prey, making it unlike any known or even possible creature. Barring any yammering about alien morality, we must assume that it is sentient and yanks human beings from stern to stem simply to be shitty. That’s horrifying, especially to a young boy seeking sense and hoping for kindness in the world.**

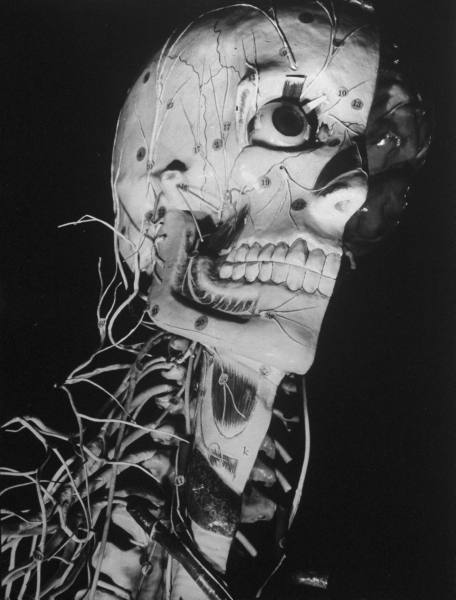

The sound effects are the second level of “The Dark’s” horror. The good doctor’s yucky description of our reversible human being is terrible enough—we’re left to imagine a pitiable anthropoid mass of veiny, sticky, red flesh, dangling organs like a grisly purse rack. Doc’s description is merely gross, but Oboler revealed his creepy genius for radio through the sudden stomach-lurching sound effect of our poor floppy guts-man trying to stand up, pitiably mewling and wetly slapping about the floor like a landed trout. Good gravy, no wonder the cop passed out.

Purportedly (though perhaps apocryphally), Oboler achieved the inside-out sound effect by filling a rubber glove with cooked macaroni and slowly reversing it Mercifully, he avoids the likelier sounds of such extreme body modification involving the bones, or the effects of reversal of the lungs and larynx. Perhaps in the words of the several dozen insensitive bastards I’ve met in my life, I’m “too sensitive,” but “The Dark” put the fix on my head for two reasons: it didn’t just make me imagine my own insides slithering out, it offered the scenario of discovering someone so reversed, and the feelings of frustrated compassion and helplessness it would entail. Gut blowout isn’t something you can kiss and slap a Band-Aid on—the first sensible reaction available to a lad of eight or nine years.

*****

Then there was that one story…

I’ll bet you have one too. A tale you read by daylight, which laid in wait in the back of your head until bedtime, emerging from the closet to say, “Hey, kid! I’m gonna keep you awake for the rest of your life. That cool?”

I read mine in seventh grade. At the time (I think I was 10) it scared the bejeezus out of me, and for years, even after maturity sapped it of fear-power, it returned in some form or other on nights that seemed excessively lonely and dark.

A great deal of its strength rested in its formatting. Someone in my class, I don’t remember who, passed along a manuscript. That’s how I remember it: a typewritten stack of eight or so pages, not a photocopy (fairly uncommon in the classroom in the late 70s), though it might have been a mimeograph; I have a memory of the ink being purple, but I can’t verify that. If it had been passed along to me as part of an anthology or a torn-out magazine page, I would have been fine. What it resembled was a sworn statement, some sort of confession, or an MS found in a bottle. I took my turn with it that night and brought it back the next day. For a long time after sleep wouldn’t come.

In summary, a young boy named Tommy is frightened of his basement, and has been so from a very young age. The door stands in the kitchen, the single room in the house where Tommy doesn’t act like a perfectly happy little fellow. When open, he screams bloody murder until mom or pop closes and locks it, taking the extra measure of stuffing the cracks in the doorframe with rags and the like, worshipping the lock with kisses and caresses. Childhood binding magic.

His parents, total yokels, are put out, and employ old-time parenting techniques like “thrashing” him and sending him to bed without his supper for this single bit of insolence. Tommy grows up, and at five years of age, in preparation for school, they take him to see the family doctor. Naturally, he is perfect health, but his basement fear is brought up. In private, Tommy tells the doctor there’s something down there, something bad, but when pressed to describe it, he reveals that he doesn’t know what it is… he just knows that IT is down there. The doc advises Tommy’s parents to nail the door open and leave Tommy in the kitchen for an hour so he’ll see his fears are groundless. Since this isn’t inspirational glurge from Reader’s Digest, you can guess where this is going.

And here was my other bout with self-doubt and potential false memory. I knew the story existed, but other than a vaguely remembered title (“The Thing in the Basement” sounded right, but seemed too vague). I couldn’t find it at the library, and I wondered whether it was the work of a classmate’s older sister or brother (hence the typewritten manuscript). The story, as I recalled it, was a perfect frame on which to hang a horror story. The tropes are all there: helpless, frightened victim whom nobody believes; a subterranean place that radiates evil; clueless authority figures—it seems like it could only exist in the abstract, as every horror story.

But. It. Did. Exist. You bless us with your beautiful bounty, oh Internet.

Whatever its provenance, David Keller’s “The Thing in the Cellar” messed with my head even more than “The Dark.” Rereading it today I see that Dr. Keller was an adequate writer who knew that while saying the monster we don’t see is more frightening than the one we do is clichéd, it’s nonetheless true. Stylistically, the story is a bit dated and clunky. The parents bug me. They’re slack-jawed, working-class rubes—what I garner from Keller’s dialogue, which is as realistic as Lovecraft’s incomprehensible rural Yankees—existing only to provide the means for their son’s destruction. Keller fears contractions, and the sentences lack flow. Maybe that was a conscious decision, but if so I don’t see what purpose it serves. From start to finish it’s like walking through a field of tall grass, stumbling on hidden rocks.

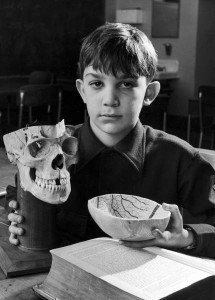

But time heals all wounds and, with luck, makes one smarter. I didn’t know Shinola about good writin’ back then. I concentrated on plot, and the plot for “The Thing in the Cellar” is scary as hell because it’s fill-in-the-blank. When you’re a child, you spend most of your time filling in blanks, often with erroneous info. See, I knew what Tommy was afraid of, I knew it because I had my own basement monsters. Somewhere I encountered a picture of a Metaluna mutant, and for a month I thought one was huddled behind the couch in my dad’s basement den. I can still it in my mind’s eye, shambling up the steps, ready to rip off my head with its claws. Now I’d probably just side-kick it back down the stairs and run like hell.

But time heals all wounds and, with luck, makes one smarter. I didn’t know Shinola about good writin’ back then. I concentrated on plot, and the plot for “The Thing in the Cellar” is scary as hell because it’s fill-in-the-blank. When you’re a child, you spend most of your time filling in blanks, often with erroneous info. See, I knew what Tommy was afraid of, I knew it because I had my own basement monsters. Somewhere I encountered a picture of a Metaluna mutant, and for a month I thought one was huddled behind the couch in my dad’s basement den. I can still it in my mind’s eye, shambling up the steps, ready to rip off my head with its claws. Now I’d probably just side-kick it back down the stairs and run like hell.

The fear got worse. I read about the “true” story of a girl who suffered periodic attacks by an invisible assailant. My unimpeachable source, by the by, was a Ripley’s Believe It… or Not! comic book, in a story titled “The Thing with Claws” (I sense a trend). My Metalunan metamorphosed into a see-through clawed assassin—the unknown became the invisible and vicious, compounded by an unseen and horrific result, namely, Tommy’s death in the story.

Ah, as for that. These two sentences stick with me to this day.

Trembling, he examined all that was left of little Tommy.

and

The mother threw herself on the floor and picked up the torn, mutilated thing that had been, only a little while ago, her little Tommy.

They sting worse now that I have kids.

We know the result of the cellar thing’s attack on Tommy—presumably a moment of joyous triumph for the creature, since it had the only being aware of its existence in its power—but we don’t know its extent. “Torn.” “Mutilated.” “All that was left.” Perhaps you’re picturing a few well-placed, deep scratches—something whipped up by the Buffy the Vampire Slayer make-up/special effects department. Not me. Not with my stupid, scared child brain. I conflated the integrity of Tommy’s corpse with a story I overheard my father telling; the one about the family who adopted a poodle as a companion to their Doberman. The next day they returned home to discover cottony viscera all across their living room rug. My child’s mind made it worse, picturing Tommy left in stringy tatters and a single red chunk of gristle staining the kitchen tiles. Tommy? Did I say Tommy?

Sorry, I meant me.

That was me.

I was there. Dead. Shredded. Violated. By the Thing in the Basement.

Rereading the story, there’s another segment that may have gotten to me. The oafish Mr. Tucker takes out his toolbox and pounds nails while explaining to his clearly terrified son in English spoken not by people who real are:

And I am going to nail the door open, Tommy, so you can not close it, as that was what the doctor said. Tommy, and you are to be a man and stay here in the kitchen alone for an hour, and we will leave the lamp a-burning, and then when you find there is naught to be afraid of, you will be well and a real man and not something for a man to be ashamed of being the father of.

Well.

I should make the point that my parents loved me and were plenty sympathetic whenever I was afraid. Mom was nurturing and reassuring; Dad rationally explained away fear—I tend to do both with my son whenever he’s afraid.*** But no kid, no adult, ever gets rid of the fear that the only thing worse than Mom and Dad not being there is Mom and Dad not giving a shit or acting, by intent or omission, as agents for one’s invisible claw monster destruction.

*****

Closing thoughts? None, really (though if anyone wants to pay me to expand on this essay, I’m all ears). When people ask me why I write—which happens ALL the damned time—I explain that I write about two subjects: what I love and what I fear. I write about what I love because I want other people to enjoy and preserve those things. I write about what I fear because, for as long as can remember, I’ve been a fearful fellow. And I don’t like it. As my former dentist told me, “Fear is the mind killer.” By reading and writing about what I fear I become not only stronger but smarter; and as I become smarter I become a better person. As personal meanings of life go, that’s not a bad policy.

As an addendum, and FYI. I’ve never mentioned the above to anyone for as long as I can remember. I figured it was time to exorcise those particular demons.

Boo!

*Also, I’m reading Stephen King’s Danse Macabre, and I’ve been itching to throw in my two, no, let’s make it nine cents on the subject.

** Side Note: I imagine Oboler had Doc specify his mouth as the final piece covered by shadows in order to avoid suggesting he was turned inside-out starting at the rectal end. Which, from an engineering perspective, makes slightly more sense.

*** My favorite technique for when Nate is afraid of something—say the giant frog-shaped shoe and sock basket on his closet door—is to punch it out and encourage him to take a few swipes himself. Mom and Dad did a good job, but I wish they’d encouraged me to go a few rounds with my monsters. In hindsight, they were all wusses.