I recently finished a double-bill of non-survivalist media by reading Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild and watching Werner Herzog’s film Grizzly Man. The thread running through both works is obvious—young to youngish fellow enters the Alaskan wilderness to escape civilization and become one with nature, eventually perishing when nature proves a terrible host. They’re both fine, entertaining works that provoke interesting debates—both external and internal. As you’ve come to expect, however, I’m less interested in discussing the works themselves than the way in which the stories were told and debated.

I recently finished a double-bill of non-survivalist media by reading Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild and watching Werner Herzog’s film Grizzly Man. The thread running through both works is obvious—young to youngish fellow enters the Alaskan wilderness to escape civilization and become one with nature, eventually perishing when nature proves a terrible host. They’re both fine, entertaining works that provoke interesting debates—both external and internal. As you’ve come to expect, however, I’m less interested in discussing the works themselves than the way in which the stories were told and debated.

Treadwell and McCandless were anti-establishment, outdoorsy fellows who preferred to sleep under the stars, live off the land, and groove on all the natures, man. McCandless graduated college, gave away all his money, and hit the road for three years, telling everyone who’d listen that he planned to rough it in Alaska’s bleak wilderness. When he finally made it, he lasted about 112 days before succumbing to starvation at the age of 23. Treadwell had a couple of decades on McCandless, was a former substance abuser, and had walked away from a failed acting career. He eventually decided to enter Katmai National Park to observe and interact with the park’s brown bear population. After 13 summers of filming and, in his mind, befriending the grizzlies, he and his girlfriend were mauled and eaten by one.

The instant reaction of most people, particularly Alaskans, was to write off both men as nut-jobs without a lick of goddamned sense. Anger is an understandable reaction. Humanity’s history is a record of divestment, not reunion, with the wild. Our species left Nature behind because Nature tried hard to kill us. The idea of entering that world without the skills, supplies, or technological advantages, humanity developed to deal with Nature’s cruelty, is romantic, yes, but also highly unrealistic—if not inane.

Looking at both men’s lives the similarities are unavoidable. McCandless was a child of privilege from a relatively stable family. Predictably growing disgusted with his life of wealth, comfort, talent, and achievement, he ran the opposite way at full tilt as soon as he came of age. For three years McCandless hoboed across America, working shit jobs and living in a tent on the outskirts of town. Like a modern My Man Godfrey, he decided living on the edge of poverty and associating with peripheral humans was somehow more real than the life he was already living.

While McCandless’ resilience and resourcefulness are impressive, his sense of duty and loyalty appeared highly mutable. Anyone reading Into the Wild will nod sadly at the stories of McCandless’ issues with his father (who, at his worst, seems to be a demanding but caring hard-ass [Later note: Sean Penn’s Into the Wild suggests spousal abuse, though it’s not entirely clear what was happening or how often.), and understand that urge to escape Daddy’s gravitational pull. But how many readers, I wonder, note that McCandless abandoned his beloved sister without a word as well?

Krakauer touches on this selfishness in his and other adventurers’ lives, but fails to make more of it. In Krakauer’s descriptions, McCandless comes across as a twitchy savant with an entirely self-constructed personality (going so far as to assume the trail name of Alexander Supertramp). McCandless engages in multiple poses as a literary rebel, vagabond, social activist, and philosopher of nature, all performed with overweening self-awareness. It’s funny then that—despite being a former college journalist and avid reader who chose to pursue a Jack London by way of Walden lifestyle—McCandless is silent, or at least non-reflective about his adventures. The grievously brief notes he left behind, scrawled in the margins of his heroes’ books, are terse unto meaninglessness. As a writer I wonder why he bothered going if he wasn’t interested in communicating what he found.

McCandless comes off as a sweet, dim, arrogant, but highly functioning kid, however, beside the sweet, dim, arrogant, but severely damaged Treadwell. While McCandless’ decision to enter the wild with minimal supplies can at be ascribed to an addle-pated search for adventure and self-actualization, Treadwell’s decision to not only live amongst the grizzlies but also approach, nay, interact with them, was incomprehensible. Watching Grizzly Man, directed by weirdo-collecting weirdo Werner Herzog, we have to opportunity to see and hear the pre-mauling Treadwell. He is sincere, excited, committed, and completely sliding off the rails. His ongoing, self-directed pep talks… His creepy baby-talk with the bears, foxes, and other critters that cross his path… His rants against the park service, which apparently dealt with him with an exorbitant amount of patience… The segment where he palpates a bear turd with an awe reserved for views of the Grand Canyon… If there’s a segment where he sounds sane, I can’t remember it.

It’s saddening, because his message—preserve nature and protect the bears—is a necessary one. By film’s end, however, you can’t really tell what good Treadwell did, or even if he was out there for reasons other than ego. His role as a filmmaker seems tacked on—a pose even—but that might be Herzog’s fault, who pastes together the hapless man’s footage to suit his needs, only commenting favorably on the parts of the film—several minutes of waving, whispering, wind-blown grass—where Treadwell is off-camera.

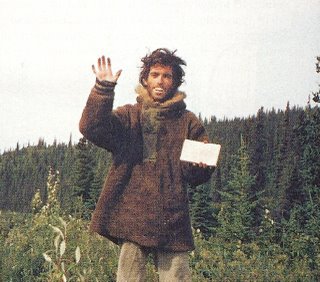

At least Treadwell has his chance to speak from beyond the grave, an opportunity not afforded McCandless’, who remains a bearded wraith in the few photographs he snapped of himself. Interestingly, I started watching Sean Penn’s film version of Into the Wild. I noted that Penn and Emile Hirsch flesh out McCandless beyond Krakauer’s series of vignettes showing “Alexander Supertramp” as a predictably rebellious post-adolescent of tremendous emotion but outstanding shallowness. If we had footage of McCandless disjointedly declaiming his adulterous father and cushy upbringing while babbling about social activism, transcendental philosophy, and Doctor Zhivago, would we find him more or less sympathetic than Treadwell? Would religions, or at least religious feelings, erupt in others?

At least Treadwell has his chance to speak from beyond the grave, an opportunity not afforded McCandless’, who remains a bearded wraith in the few photographs he snapped of himself. Interestingly, I started watching Sean Penn’s film version of Into the Wild. I noted that Penn and Emile Hirsch flesh out McCandless beyond Krakauer’s series of vignettes showing “Alexander Supertramp” as a predictably rebellious post-adolescent of tremendous emotion but outstanding shallowness. If we had footage of McCandless disjointedly declaiming his adulterous father and cushy upbringing while babbling about social activism, transcendental philosophy, and Doctor Zhivago, would we find him more or less sympathetic than Treadwell? Would religions, or at least religious feelings, erupt in others?

McCandless and Treadwell have their defenders (residents of the edge who favor ambiguity and taking risks without taking precautions always will), but this is not surprising. It’s a human quality to look at the more romantic segments rather than the whole of lives like McCandless’ and Treadwell’s. The positive reaction to their “sacrifices” goes back centuries. We see it with the Christian Desert Fathers—often wealthy men (the poor already know only sacrifice, after all, which somehow cheapens it) who shed their worldly possessions, cut off ties with their families, and entered the wilderness to search for a greater connection with God and personal and spiritual gnosis through self-denial. To a part of the human population, any human willing to subject him or herself to suffering must be extraordinary—ordinary people just don’t do things like that.

People traveled through inhospitable climes and environments just to chat with St. Anthony the Anchorite through the crack between the tomb he lived in and the boulder rolled in front of it. I wonder what he told them that kept them coming? Probably a reiteration of the example of Christ and his admonishment to reject worldly things, take up your cross, and join him. Not that Jesus was an original thinker in that regard. Diogenes suggested the same thing, albeit in a nastier way. But according to legend even Alexander the Great was in awe of that foul-smelling, -speaking, and -behaving cynic, saying that if he couldn’t be Alexander he would want to be Diogenes. Again, anyone so off-putting must be on to something. We must seek their approval; we must realize we can never achieve the pain and failure they’ve experienced. That didn’t prevent Alexander from ruling the known world, of course.

Unconditional compassion is a worthy goal, but it often becomes entangled in rationalization. People can be so compassionate it blinds them to incredibly asinine behavior. I find it staggering that in the face of the evidence—McCandless’ insistence on not carrying the basics for wilderness living; Treadwell’s anthropomorphizing of the Katmai bears—people continue to sew angel wings onto them. No one’s life should be defined or criticized for a single act of self-injuring foolishness; but systematic, life-ending foolishness? Hell, it should be open season on that all year long.